Happy Monday, folks! It’s been a hot minute since we’ve had a Monday Morning Thoughts blog post, but it happens. What can I say?

Chronic infection is a killer in cystic fibrosis. It’s widely accepted that although infection rates are slowly decreasing across the community (maybe thanks to kids getting on CFTR modulators before their disease starts to progress?), multidrug resistant infections and troublesome infections (like mycobacteria), are holding steady or slightly increasing (see 2017 CFF Patient Registry).

Cystic Fibrosis Foundation is aware of this problem in a big way, and doing whatever they can to incentivize the creation of new antimicrobials. It’s an uphill fight, though. There’s currently little incentive from our government (and this has been the case for a long, long time) for drug makers to dive into the market. Eventually that will have to change.

In the meantime, though, is it possible that we might already have a viable weapon to use in the fight against some of these drug-resistant bacteria?

I’ll answer that for you…

Yes. The weapon exists and we know how it works.

Enter, bacteriophages (phages for short).

The war between bacteriophages and bacteria has been going on for millions of years, and it will continue long after we’re gone. What is a bacteriophage?

From Harvard:

Phages are viruses that infect only bacteria. As a type of virus, phages cannot live and reproduce alone. Viruses need to invade a host cell, consume the host’s nutrients to make more copies of themselves, and lastly get out of the host cell – often by killing the host in the process…phages are able to kill antibiotic-resistant bacteria. The way that phages kill bacteria is harder for bacteria to develop resistance against compared to the way that antibiotics kill bacteria. Rather than stopping bacteria from doing one specific process like in the case of antibiotics, phages actively destroy the bacteria’s cell wall and cell membrane and kill bacteria by making many holes from the inside out. In addition, many bacteria develop biofilm – a thick layer of viscous materials that protect them from antibiotics. Many phages are equipped with tools that can digest this biofilm.

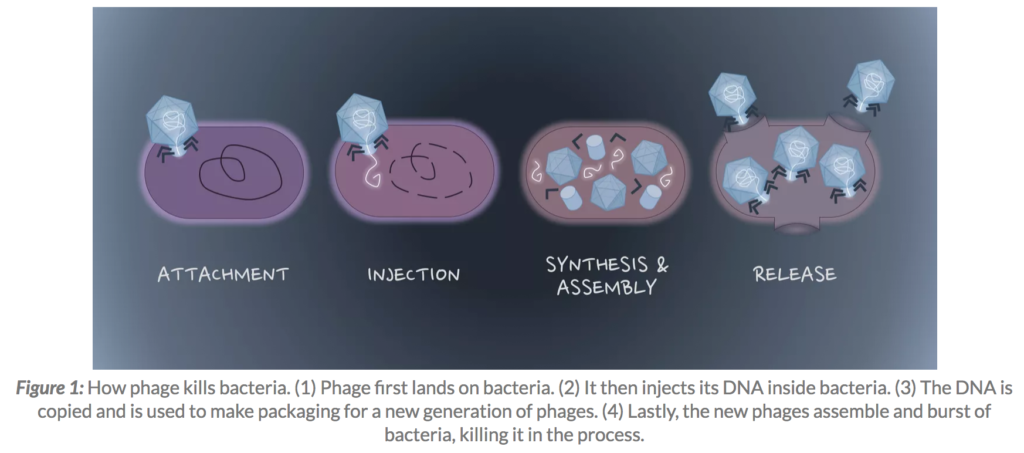

Enjoy this sweet info graphic simply detailing how a bacteria phage injects its DNA into host bacteria to destroy it:

Bacteriophages are one of those things that you hear about from your aunt’s weird friend at Thanksgiving dinner. They have a bit of a snake oil vibe about them because they’re naturally occurring. Our culture dismissed them because of the rise of antibiotics. The most unfortunate thing about phages is that they caught on right before the discovery of penicillin. Penicillin’s wide use and seemingly universal effectiveness in the early part of the 20th century overshadowed what phages are capable of achieving.

Sadly, as we now know, antibiotics are only as good as their sensitivity (and allergy!!!) profiles.

Phages got some play in CF about a year ago when Mallory Smith’s family and care team made a desperate plea to get phages in a last ditch effort to contain her out of control Burkholderia cepacia infection after all antibiotics had failed.

Sadly, Mallory Smith didn’t survive the wait. She was 25.

Phages are back in the headlines, however. Following an emergency appeal, researchers from Yale successfully treated Paige, a young woman with CF, whose infection had become completely resistant to antibiotics.

Below you’ll find a super basic, easy-to-understand video that followed Paige’s case. I recommend taking 12 minutes to watch the video.

A single inhaled treatment session suddenly turned around Paige’s antibiotic resistance problem. Simply put, she has regained the power of antibiotics in her battle with cystic fibrosis and chronic infectious disease.

It almost seems too good to be true. Maybe it is?

There’s a massive barrier to widespread phage use in the medical world. Bacteriophages embody the term, “precision medicine.” Phages have to be individually tailored to treat patients. Phages have to be grown against host bacteria in the petri dish and then isolated before they can be introduced into treatment, and it’s not quite as simple as going to the phage store to pick out the perfect fit for your pseudomonas strain. The work is labor intensive for the folks who are building a patient’s phage treatment. It’s not quite the same thing as broad-spectrum use, like Levaquin, for example, where a doctor calls in the same medication that’s suitable for half a thousand people on a given day.

Phage therapy does have a few safety hurdles as well. Widespread use in cystic fibrosis would require intense scrutiny from our regulators since there’s no large dataset to prove otherwise. Although most people with intimate knowledge around phages claim there are few safety concerns, it’s not appropriate to start dosing people on something that hasn’t gone through the system.

Other hurdles include drug patents. Patenting something that is naturally occurring isn’t quite the same thing as branding a cocktail medication.

The idea that phages are a bit of witchcraft comes from the notion that they have to be individually made for people. Quite literally, researchers are using a little of this and little of that to create treatments for people. It also probably doesn’t help out our cause that phages are considered eastern medicine. The west has a general distrust of things that are not meticulously scrutinized by our FDA and regulators. Maybe that will change?

So, what do I think about phages? I suppose this is my blog, and I should give an opinion after all.

I think this technology is legit. That doesn’t mean you need to head over to Tiblisi, Georgia (the home of phage therapy!) and start yourself on some wild goose chase. I do think phages will catch on here in the US, especially if the success the Yale researchers demonstrated can be replicated in more people with CF and infectious disease. I think it would do you justice to learn as much about phage therapy as possible, so you can be armed with the appropriate resources to question care teams and Cystic Fibrosis Foundation.

The days of your weird aunt being the only one to know about phages are coming to a close. Infectious disease is still killing people with CF despite our progress with the CFTR modulators, and it’s important we continue to make our medication arsenal as robust as possible. Continued proven success with phages will push people to this cause. We need to start talking about phages, and bring down the alternative remedy stigma that exists around them. Bacteriophages have been waging a war against harmful bacteria for millions and millions of years… this is the real deal.

Want to know more about phages? Let me know in the comments, and I’ll keep you updated on my study of the topic!