Last week I naively asked, “Will we fall victim to healthcare rationing?”

This week it seems like that’s the question global experts are asking, too.

The thing that scares me most about the coronavirus outbreak is the potential for an indefinite period of time where every day health services could be out of reach. Yes, the virus, itself, is scary, but what really gives me pause is the pressure weighing on the health system’s capacity.

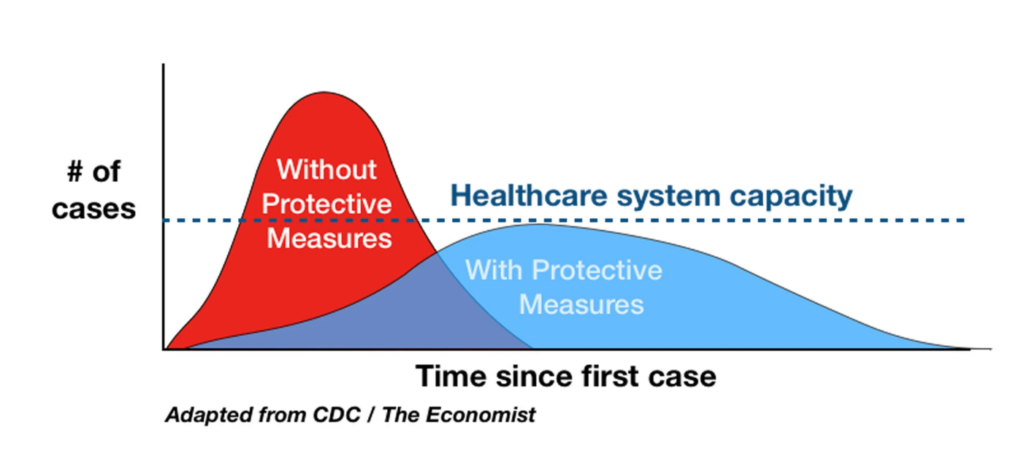

Regardless of how you have gotten your news over the past few days, you’ve probably heard or seen the phrase “flatten the curve.”

Here’s the curve:

It’s a rough sketch of how collective cases during an epidemic can quickly overrun health services – the very thing happening in Northern Italy right now, just like it happened in Wuhan – compared with a controlled number of cases drawn out over time.

The New York Times explains it best:

“Think of the health care system capacity as a subway car that can only hold so many people at once. During rush hour, that capacity is not enough to handle the demand, so people must wait on the platform for their turn to ride. Staggering work hours diminishes the rush hour and increases the likelihood that you will get on the train and maybe even get a seat. Avoiding a surge of coronavirus cases can ensure that anyone who needs care will find it at the hospital.”

In Italy, The Atlantic reports that the subway car is bursting, and, well, it’s too hard for me to write about how they are triaging patients there. You can read the article if you want.

Flattening the curve protects the capacity of the health system.

Of course, the thing that is most unsettling when looking at the graph – whether it’s the huge amount of cases for a short period of time or relatively fewer cases over a longer period of time – is the distribution of risk for the elderly and the sick remains skewed. Until there is a functional vaccine or treatment, we rely on population health.

Maybe that’s what is a little scary. In the absence of herd immunity, the people with the highest risk for severe disease are reliant on people who don’t assume the same kind of risk for severe disease in the short term.

The coronavirus doesn’t live in a vacuum, though.

Hospital beds are already occupied for any number of reasons.

People, like those of us with CF or folks who break a bone or people who are reliant on dialysis or any number of medical needs, use all sorts of medical infrastructure. If the public doesn’t take steps to “mitigate” the spread of coronavirus, then the health services that we rely on could be bottlenecked, unreachable, or, in the worst case, offline as coronavirus patients become the only priority. The thought of developing a pulmonary exacerbation for any reason – maybe it’s the flu, the common cold or a new bacterial culture – during a time when those services aren’t readily available is almost unthinkable.

That’s why I am feeling anxious.

It feels like the world has changed in a matter of a week, and abrupt change is scary.

Hell… it feels like everything changed in the matter of a hours. From the president’s address to Tom Hanks telling the world he tested positive and the NBA suddenly having to suspend the season after an arena was evacuated because a player tested positive for COVID-19, everything is happening so quickly.

We all have to work together to flatten the curve. Yes, we will rely on the healthy population to do their part. I hope that the major turn in events tonight caught everyone’s attention. Yes, experts are saying it will get worse before it gets better. When you turn on the news or read another blog or article, know that. We will have to push through the storm together.

Continue to monitor messaging from CF organizations, the CDC, your CF clinics and medical centers. Hold each other up, work together, and remember, when it’s time to make a decision, do your best to be level headed and clear minded. The virus is here whether we like it or not, we’re going to have to take it on.