Medical security is one of the most fundamental rights offered to patients and the medical system. Patient privacy is why I often omit or generalize different medical details about my own life within these blogs. I don’t write about PFT scores, test results and things like that.

It’s also why I never tried to track down the identity of the doctor-gone-rogue (remember, the healthcare worker who broke isolation and exposed a bunch of Tuck students back at the beginning on March) nor would I speculate beyond the information publicly released. I think he is as entitled as anyone to the same privacy as anyone else flowing through the health system.

In this age of hyperawareness, I wonder, though, where we draw the line for patient privacy as we glean to learn more about the coronavirus to protect our loved ones.

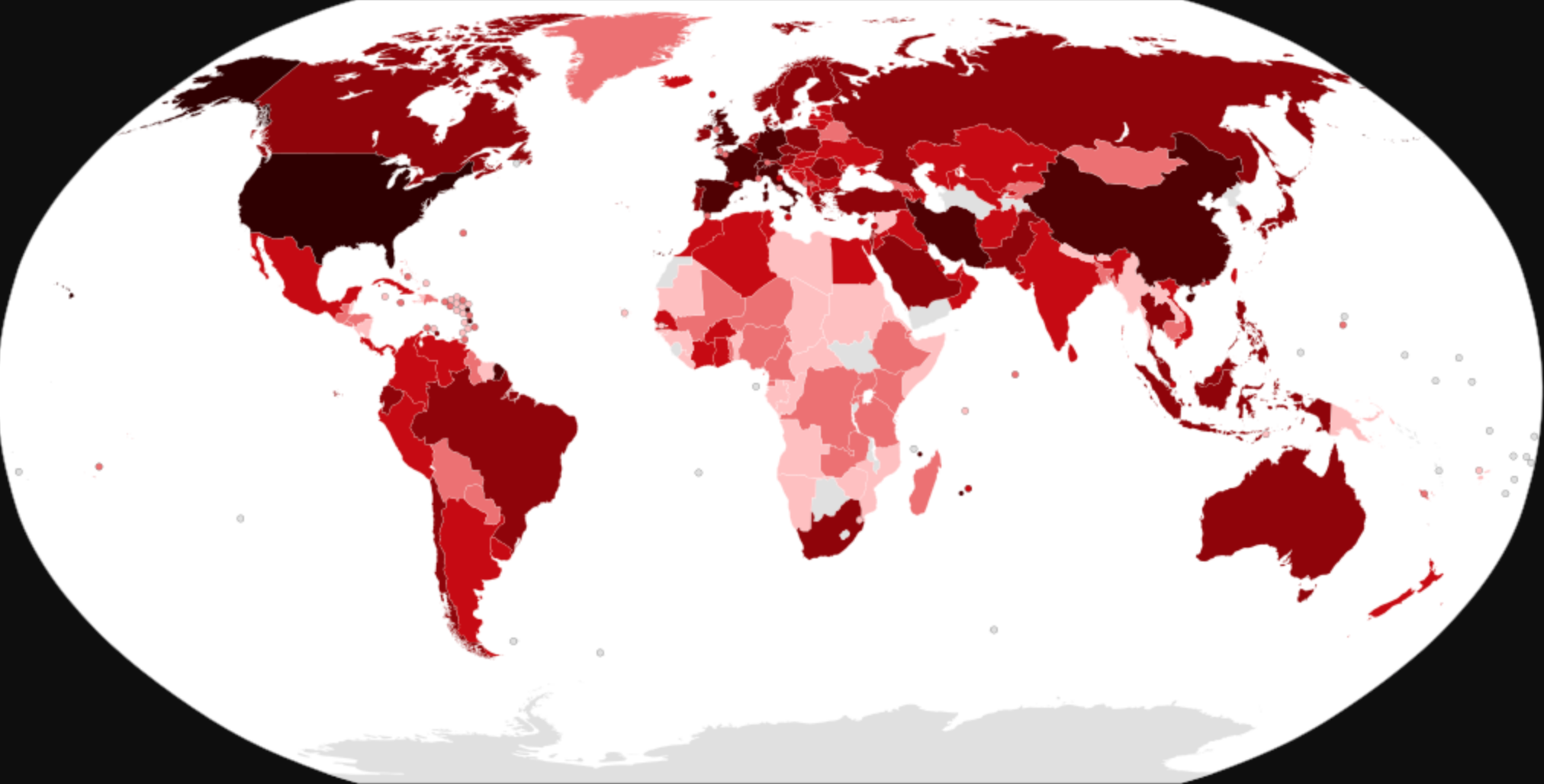

Surely you have seen the interactive maps tracking COVID-19 cases by county like the one from Johns Hopkins, or maybe you have seen your local news publish maps with coronavirus cases by township, like Newsday’s map of Long Island.

The maps are a certain blend of precise location based data and vagueness. They don’t tell you much about who has the disease, how they are doing, and where they are relative to your life.

Instead, we wait on the edge of our seats for the fateful call from a friend or family member (or the department of health) to tell us we have been exposed to a confirmed case.

Do we have the right to know if our neighbors are suffering from the coronavirus? What are the consequences of learning that an employee at your favorite no-touch coffee shop was stricken with COVID-19 three weeks ago but has since recovered? What can be learned from demographic data collection in this time of crisis?

There is much to be learned about the coronavirus, namely, why does it affect some so harshly, but seems to spare others? The tragic story of the New Jersey family who has suffered beyond reason to COVID-19 with four family members dead and nearly a dozen sick would almost suggest there is something genetic about acquiring the illness. While the almost perfectly controlled Diamond Princess offers a very different tale about the virus’s attack rate. Then, of course, there are the super spreaders who transcend all of the above.

I firmly fall in the “patient privacy” camp. Under no circumstances should patients be publicly named in the discussion about their condition (unless they’d like to be). The growing stigma around COVID-19 could make patient lives more hellish than they probably already are, and lead to a nightmarish return to their lives after recovery. BUT I think it is justified to paint a picture about the risks people may face in their communities. Residents should be made aware if a close neighbor on their street or in their building has the coronavirus so that people may have the opportunity to protect themselves. After all, social distancing succeeds when populations put distance between the disease and potential vectors. I periodically check the New Hampshire state COVID-19 site to check in on the state of the pandemic in Grafton county (where Dartmouth is located). The highly blinded data fed to the public, though, leaves me with little evidence to support the steps I take to protect myself.

I am conflicted. On one hand I crave more localized demographic and genetic data, but I feel that patient privacy is paramount if we hope to maintain our current interpretation of patient protection laws. So I ask you, what is more important? Secure patient privacy or open data to help you inform choices?