Gene therapies are coming, and they are coming fast! That’s in part because Vertex has proven the market for restoring CFTR function is healthy and profitable. So much so that a lot of companies are jumping in. A quick look at the pipeline (multiple pipelines apparently because it seems like the CFF’s is missing a few) shows something between a dozen and two dozen companies working on gene therapy or gene editing (and mRNA-based) technologies designed to restore CFTR function. This is especially important for the non-modulated CF population because that’s the target population for most of these drug makers. It is also going to force us to ask some tough questions, namely, how can someone interested in participating in a gene therapy clinical trial know they are enrolling into the trial that is not only the best for them, but also the community at large?

This all boils down to a “supply” problem. That is, of course, a supply of trial participants. The trial opportunities are going to come flying in, but there’s going to be a small participant pool to choose from. Simply, when a person decides to participate in a study, a competing drug maker has one fewer eligible person it can use for its own study.

For gene therapies, this problem is magnified because they have notoriously long follow-up times for safety and efficacy testing. In plain English, that means once you’re in a gene therapy clinical trial, you’re in it for the long haul without the chance of unenrolling and switching to another opportunity. In a lot of ways, this is a good problem because the number of shots on goal is increasing for those who can’t use modulators. But it is a problem that patients need to keep front of mind. The sad reality is that most drug trials fail, so choosing the right clinical trial is of paramount importance. But how?

First, some back of the napkin math shows what I’m talking about.

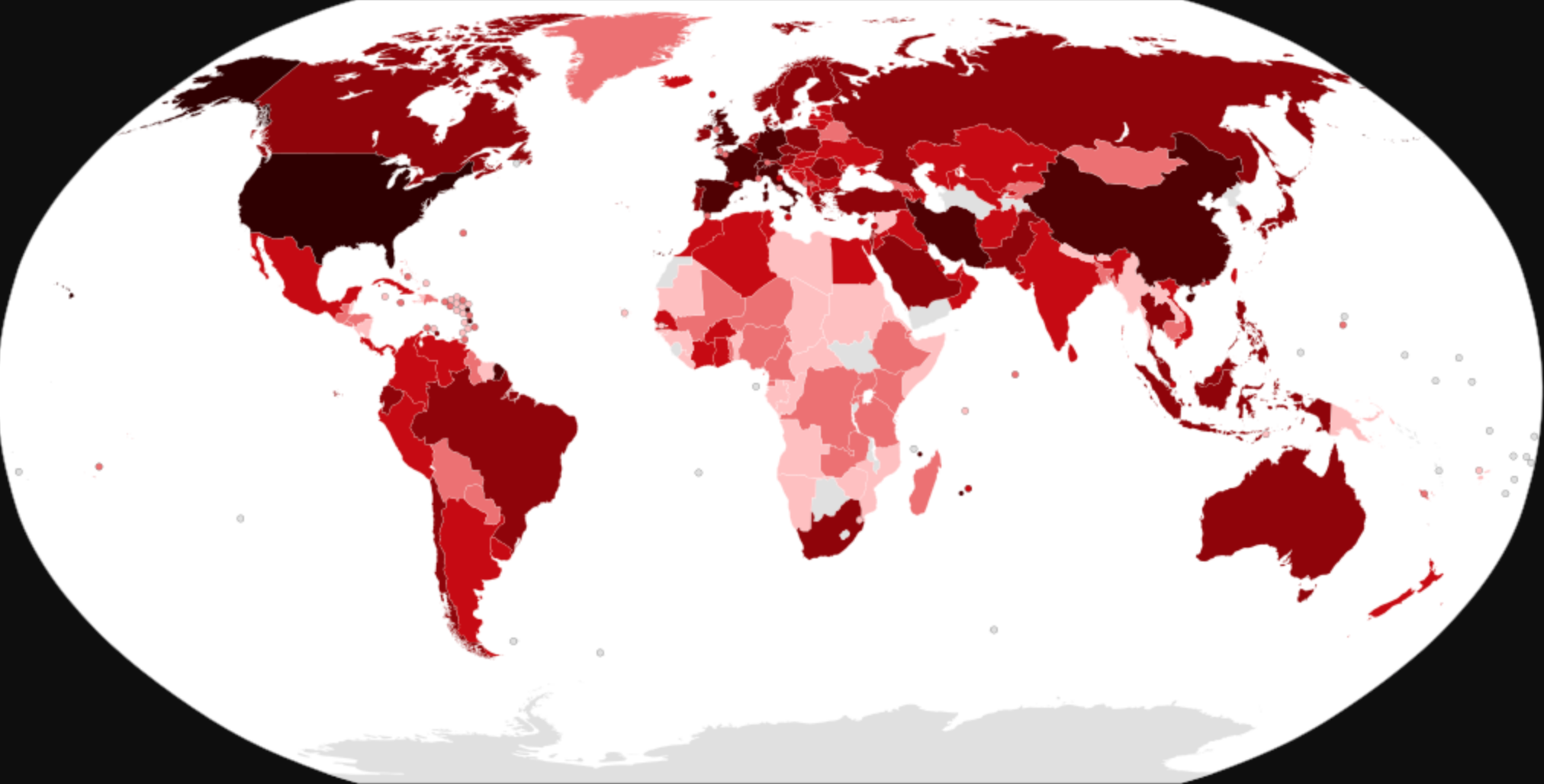

There are about 15 companies looking at getting into the clinic over the next several years.

In the US, there about 4,000 people (10% of the population) with CF who are not eligible for modulator therapy. That 4,000 number represents the US market size for these companies (which also leads to some complex questions around drug pricing and access… think Trikafta has a high list price? Just wait…).

For most of these patients, the reason they are not eligible for CFTR modulators is because their mutation combinations don’t lead to the production of the CFTR protein. That means, their bodies need to be conditioned to produce functioning CFTR (whereas the modulated population has dysfunctional CFTR that can be corrected). Genetic medicine technologies are the leading contenders to solve that problem.

4,000 US patients is a small trial population, but it’s even smaller when you slice it by age. Assuming the age demographics of the non-modulated population are like that of the broader population (the survival curves likely haven’t split yet because of how new highly effective CFTR modulators are), you’re looking at a little more than 2,000 US patients indicated for future studies when you consider inclusion criteria (give or take a few hundred. Back of the napkin math here). Of course, people x-US will also play a role here, but only in places where the healthcare delivery systems are advanced enough to deliver and staff complex trials for genetic medicines. All in, my best guess is that we’re going to be looking at something between 3,000 – 5,000 potential participants across a handful of countries to lead the charge into the era of CF genetic medicines. Yes, some people on, or eligible for, highly effective modulator therapy might want to get themselves into these trials, too, but this first wave of genetic medicines will need to be as good or better than the standard of care with Trikafta. Time will tell if that’s going to be the case.

No matter how you slice it, 3,000 – 5,000 trial participants is a small group, and I can’t think of another indication (outside of some specific cancers, maybe?) that is as crowded as non-modulated cystic fibrosis with companies trying to tackle this unmet need (and I’m not even counting future mutation agnostic therapies like anti-infectives and the like). The good news is that given the small population pool, these trials probably won’t need to be huge to demonstrate small changes in FEV1 as an endpoint, and there are some strategies to enhance each participant’s impact (some ideas on that below).

As a point of reference, the trial that led to the approval of Trikafta had about 400 patients in it. These will necessarily need to be smaller. But even so, a pretty significant part of the 3,000-5,000 patients that will be presumably targeted for therapies will need to be motivated to participate.

So, what does this mean for patients? It means you need to be thinking about this now. Over the next couple of years you’re going to hear more and more about cystic fibrosis gene therapies (I’m using the term to be inclusive of gene editing and mRNA medicines), and it’s going to be exciting. But it’s important that you learn how they work, how frequently they are dosed and by which method, the differences between them, what their clinical trial protocols will look like, and, if you can, attempt to figure out their chances of success based on earlier clinical readouts or candid conversations with CF providers on the front lines of clinical trials. I call this smart clinical trial enrollment. It’s rare that people have so many opportunities to choose from, but in this case it gives participants the leverage to pick winners. People will pick with their names on the informed consent pages.

For companies, this also presents a challenge. Competitive enrollment is going to be the name of the game. Delayed or slowed enrollment can quickly increase the cost of facilitating a clinical trial, so much so that solvency becomes an issue. CF gene therapy makers aren’t going to get the luxury Vertex had with quick and clean enrollments during the modulator trials. So how can companies do that without unduly influencing participants? It means they need to be crystal clear about what their working on with community members. They will need to candidly talk about their trial design choices and solicit feedback from patient partners at the earliest parts of product development. They’re also going to need to talk about their therapy’s place in the CF care routine (if they understand it), and what its intensity might look like. The time is now for these companies to abandon industry jargon and meet patients where they are with clearly articulated messaging.

It’s an exciting time in cystic fibrosis and it’s going to be especially exciting to see how these clinical programs play out. Importantly, there are a few methods for reducing the enrollment burden for such a small population through something akin to a platform trial or by using synthetic control arms. Those are two trial designs that basically increase the utility of placebo control arms and could require fewer patients to be on a placebo. They’d require cross-industry collaboration, but I think it’s something the CF Foundation’s clinical trial network could pull off. If something like that ends up being the path forward, it would, yet again, be an example of the cystic fibrosis community leading the charge into future of clinical trials.